HFR: Who were some of your early mentors or teachers?

FP: The first poet I worked with was the late Paula Rankin. She was the person who saw potential in my work and, at the time (around 1986-87) that was quite a feat! Paula, in time, introduced me to the poet Richard Jackson. Rick was teaching in the low-residency program at Vermont College and, after a brief stint in graduate school at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, I decided to transfer to Vermont. I couldn’t’ have made a wiser move. The poets I worked with were all incredibly talented writers and teachers. I worked with Rick Jackson my first semester. Subsequently, I studied with Mark Doty, the late Lynda Hull and, finally, David Wojahn.

HFR: When you write a poem, what is your process?

FP: It can be exhilarating. It can be hellish. Most of the time, the hellish aspect comes into play when I have not yet managed to start a poem. I agonize over what I am going to write. I often doubt I will be able to write a poem ever again. That can be quite brutal. It’s certainly not a happy state of affairs.

I keep a notebook in which I write down ideas for poems. Just a word or two. For example, if I’m reading a book and I find something of particular interest (an historical incident, perhaps) I might just write a note about that. I think part of my mind begins to work at that point—but it’s all subconscious. Weeks, or even months later, I flip through the notebook and am reminded of my earlier intention to write a poem about “x.” If I’m still interested in doing that, I might sit down and try to begin. And that’s the hellish part I mentioned earlier.

Oftentimes, it can take hours for me to write as much as a single word. I sit and stare out the window. I shift. I decide to do things that don’t really need to be tended to just to get away from the task at hand. I really can’t stress how awful it can be for me.

Fortunately, there comes a point where I enter a state of consciousness that is different from my norm. I know that might sound mystical or whatever you’d like to call it—but it really is the case. That’s when I can begin writing and that is generally when the pleasure begins. I write and then, at some point, I sit back and read over what I’ve just written. Until recently, I had to do this longhand. It was only after I had a fairly well-shaped poem that I could switch to the computer, but lately I’ve been working directly on my computer after I get a little bit down longhand and that’s been working quite well. It allows me to play with line breaks much more readily and that can move a poem in a different direction.

Without a doubt, the best part of writing, for me, is the revision process. I really love going back and fine-tuning my language, line breaks, deleting things, moving them around, et cetera. It’s when I am revising that I can best practice the craft of poetry.

HFR: Do you have a specific revision strategy? Are there things you watch out for in particular? How do you know when a poem is “finished?”

FP: No, I don’t have a specific revision strategy. Once I have a rough draft of a poem, I just look at what’s on the page and try to determine those places where it isn’t really singing yet. Sometimes I’ll notice the line breaks are slowing things down too much when they need to go faster, or speeding them up when they need to be slower, so I’ll work on those. Or maybe I’ll realize I’m assuming the reader will know something they very well might not—so I’ll have to fill in a gap. It all depends.

One thing I consistently look for is easy language—clichés, or simply instances where I know I could torque the language. I want my poems to be as beautiful as I can make them even when the subject matter isn’t beautiful. I like my poems to sing whether that song is joyous or a dirge.

As for knowing when a poem is finished—well, that’s a really great question. I sometimes think none of my poems are ever really finished. I can look back on older pieces and see places where I could have done better. I guess it becomes a matter of deciding I’ve done the best I can do at the time. At some point, I have to let a poem go and move on. The trick is getting as close as I can to having it feel right. Once I achieve that, I let it be. If a poem is going to be in one of my books, I get a final chance to change a thing or two here and there if I feel it will be helpful, but basically, once I feel I’ve got things in the best possible shape, I have to let it go.

HFR: In many of your poems, in particular “Horse Latitudes,” “Rehearsals,” and “Mercy,” animal life seems prized over human life. “Horse Latitudes,” in fact, seems an elegy for the horses—a sort of apology—as opposed to an elegy for suffering or the loss of human life. Could you talk about your beliefs concerning animals, and what they mean to you, particularly in your poetry?

FP: I don’t at all agree that animal life is shown to be more valuable or worthwhile than human life in my work. It certainly has never been my intention to make such a judgment. In “Horse Latitudes,” both the speaker and the woman he addresses are compared to the horses that are discarded in favor of human life. There was no intention to make a pronouncement on the morality of that decision, but merely to draw the parallel and leave it at that. The rabbit in “Rehearsals” is killed because it is ill. No judgment there, either. And I think “Mercy” is also non-judgmental. It points out the fact that these horses are being thrown overboard because the humans on board need to take advantage of whatever breeze might be available—but they aren’t happy about needing to kill the horses.

HFR: I think we sensed that in your work because the animals themselves are considered with such esteem they do seem to have a value beyond themselves. Could you talk a little more about your perception of animal/human relationships in your poems?

FP: What comes immediately to mind is the nobility I see in animals. I don’t mean to suggest it’s conscious—though it may be for all I know—but I see in many animals qualities that most humans don’t even come close to possessing. They live very much in the moment. No past. No future. Just what’s here and now. There’s something very appealing in that thought. They also seem to have a capacity for a kind of love I also don’t see displayed by too many humans. It’s the kind of unquestioning, unconditional love you can get from a pet. Beyond that, there is the grace of animals. I love horses. I love to see them run. There’s nothing more graceful that I can imagine…all that sleek muscle, sweat-sheened fur and flowing manes.

And maybe some people will think this is horrible—but so be it—when I think about situations like the ones presented in “Horse Latitudes,” and “Mercy,” I personally think, were I the captain, I’d have a hard time not throwing certain people overboard before the horses.

HFR: Some of your poems seem deeply personal, such as the poems in Out of Eden that deal with the death of your father (“The Truth,” and “Halfway,” in particular). Most of your poems, though, seem distanced from your biography. How do you negotiate the personal in your poetry?

FP: That’s an interesting question, and one I have been trying to answer for myself. So far, I haven’t come up with much. I think part of the answer might lie in the fact that I don’t’ think people will necessarily be interested in autobiographical poems. That might be untrue, but sometimes I feel it is true.

In a larger way, though, I think it has to do with my own philosophy about poetry. It’s dangerous to think your reader will be enthralled or even interested in what goes on in your personal life. The challenge of writing is to make whatever I am writing about matter to my reader. After all, I am not writing for myself only. Yes, I do write for my own pleasure and to discover truths through the process of thinking things through in my poems, but I wouldn’t get much satisfaction out of it if I didn’t feel someone might actually connect with whatever it is I am saying. That, I think, is how I come to determine whether or not my own life might be game for poetry.

HFR: Many of your poems seem to be written in persona voices—for example, “Ophelia,” “Leda,” and “Denali.” Do you give special consideration to writing gendered voices?

FP: The first poet I worked with was the late Paula Rankin. She was the person who saw potential in my work and, at the time (around 1986-87) that was quite a feat! Paula, in time, introduced me to the poet Richard Jackson. Rick was teaching in the low-residency program at Vermont College and, after a brief stint in graduate school at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, I decided to transfer to Vermont. I couldn’t’ have made a wiser move. The poets I worked with were all incredibly talented writers and teachers. I worked with Rick Jackson my first semester. Subsequently, I studied with Mark Doty, the late Lynda Hull and, finally, David Wojahn.

HFR: When you write a poem, what is your process?

FP: It can be exhilarating. It can be hellish. Most of the time, the hellish aspect comes into play when I have not yet managed to start a poem. I agonize over what I am going to write. I often doubt I will be able to write a poem ever again. That can be quite brutal. It’s certainly not a happy state of affairs.

I keep a notebook in which I write down ideas for poems. Just a word or two. For example, if I’m reading a book and I find something of particular interest (an historical incident, perhaps) I might just write a note about that. I think part of my mind begins to work at that point—but it’s all subconscious. Weeks, or even months later, I flip through the notebook and am reminded of my earlier intention to write a poem about “x.” If I’m still interested in doing that, I might sit down and try to begin. And that’s the hellish part I mentioned earlier.

Oftentimes, it can take hours for me to write as much as a single word. I sit and stare out the window. I shift. I decide to do things that don’t really need to be tended to just to get away from the task at hand. I really can’t stress how awful it can be for me.

Fortunately, there comes a point where I enter a state of consciousness that is different from my norm. I know that might sound mystical or whatever you’d like to call it—but it really is the case. That’s when I can begin writing and that is generally when the pleasure begins. I write and then, at some point, I sit back and read over what I’ve just written. Until recently, I had to do this longhand. It was only after I had a fairly well-shaped poem that I could switch to the computer, but lately I’ve been working directly on my computer after I get a little bit down longhand and that’s been working quite well. It allows me to play with line breaks much more readily and that can move a poem in a different direction.

Without a doubt, the best part of writing, for me, is the revision process. I really love going back and fine-tuning my language, line breaks, deleting things, moving them around, et cetera. It’s when I am revising that I can best practice the craft of poetry.

HFR: Do you have a specific revision strategy? Are there things you watch out for in particular? How do you know when a poem is “finished?”

FP: No, I don’t have a specific revision strategy. Once I have a rough draft of a poem, I just look at what’s on the page and try to determine those places where it isn’t really singing yet. Sometimes I’ll notice the line breaks are slowing things down too much when they need to go faster, or speeding them up when they need to be slower, so I’ll work on those. Or maybe I’ll realize I’m assuming the reader will know something they very well might not—so I’ll have to fill in a gap. It all depends.

One thing I consistently look for is easy language—clichés, or simply instances where I know I could torque the language. I want my poems to be as beautiful as I can make them even when the subject matter isn’t beautiful. I like my poems to sing whether that song is joyous or a dirge.

As for knowing when a poem is finished—well, that’s a really great question. I sometimes think none of my poems are ever really finished. I can look back on older pieces and see places where I could have done better. I guess it becomes a matter of deciding I’ve done the best I can do at the time. At some point, I have to let a poem go and move on. The trick is getting as close as I can to having it feel right. Once I achieve that, I let it be. If a poem is going to be in one of my books, I get a final chance to change a thing or two here and there if I feel it will be helpful, but basically, once I feel I’ve got things in the best possible shape, I have to let it go.

HFR: In many of your poems, in particular “Horse Latitudes,” “Rehearsals,” and “Mercy,” animal life seems prized over human life. “Horse Latitudes,” in fact, seems an elegy for the horses—a sort of apology—as opposed to an elegy for suffering or the loss of human life. Could you talk about your beliefs concerning animals, and what they mean to you, particularly in your poetry?

FP: I don’t at all agree that animal life is shown to be more valuable or worthwhile than human life in my work. It certainly has never been my intention to make such a judgment. In “Horse Latitudes,” both the speaker and the woman he addresses are compared to the horses that are discarded in favor of human life. There was no intention to make a pronouncement on the morality of that decision, but merely to draw the parallel and leave it at that. The rabbit in “Rehearsals” is killed because it is ill. No judgment there, either. And I think “Mercy” is also non-judgmental. It points out the fact that these horses are being thrown overboard because the humans on board need to take advantage of whatever breeze might be available—but they aren’t happy about needing to kill the horses.

HFR: I think we sensed that in your work because the animals themselves are considered with such esteem they do seem to have a value beyond themselves. Could you talk a little more about your perception of animal/human relationships in your poems?

FP: What comes immediately to mind is the nobility I see in animals. I don’t mean to suggest it’s conscious—though it may be for all I know—but I see in many animals qualities that most humans don’t even come close to possessing. They live very much in the moment. No past. No future. Just what’s here and now. There’s something very appealing in that thought. They also seem to have a capacity for a kind of love I also don’t see displayed by too many humans. It’s the kind of unquestioning, unconditional love you can get from a pet. Beyond that, there is the grace of animals. I love horses. I love to see them run. There’s nothing more graceful that I can imagine…all that sleek muscle, sweat-sheened fur and flowing manes.

And maybe some people will think this is horrible—but so be it—when I think about situations like the ones presented in “Horse Latitudes,” and “Mercy,” I personally think, were I the captain, I’d have a hard time not throwing certain people overboard before the horses.

HFR: Some of your poems seem deeply personal, such as the poems in Out of Eden that deal with the death of your father (“The Truth,” and “Halfway,” in particular). Most of your poems, though, seem distanced from your biography. How do you negotiate the personal in your poetry?

FP: That’s an interesting question, and one I have been trying to answer for myself. So far, I haven’t come up with much. I think part of the answer might lie in the fact that I don’t’ think people will necessarily be interested in autobiographical poems. That might be untrue, but sometimes I feel it is true.

In a larger way, though, I think it has to do with my own philosophy about poetry. It’s dangerous to think your reader will be enthralled or even interested in what goes on in your personal life. The challenge of writing is to make whatever I am writing about matter to my reader. After all, I am not writing for myself only. Yes, I do write for my own pleasure and to discover truths through the process of thinking things through in my poems, but I wouldn’t get much satisfaction out of it if I didn’t feel someone might actually connect with whatever it is I am saying. That, I think, is how I come to determine whether or not my own life might be game for poetry.

HFR: Many of your poems seem to be written in persona voices—for example, “Ophelia,” “Leda,” and “Denali.” Do you give special consideration to writing gendered voices?

FP: I give absolutely no thought to writing gendered voices. I am only interested in writing about those things that captivate me and that I think will captivate others on some level, too.

HFR: How do you know whose voice you are writing in? What elements make a voice sound authentic to you in your poems?

FP: Without trying to sound flip, I know whose voice I am writing in because it’s the voice I’ve chosen to write in. Or the voice that has chosen me to be its scribe.

Authenticity is elusive. In a sense, I have only my imagination to guide my hand. But there’s another, more mystical aspect, which is almost a kind of possession or surrender. I try to allow the personality of the individual to flow through my hands. In the same way, I try to inhabit historical events I might be writing about. Again, the aim is to paint a picture for myself and for my readers. If I achieve that—a vivid picture—I guess that’s authenticity.

HFR: The second section of Out of Eden consists entirely of elegies, ranging from poems about Keats, to Oscar Wilde, to Isadora Duncan. In the second section of The Rapture of Matter you elegize Shelley, your cousin, your father, mountain climbers, and Mike, a young man who commits suicide. What does the elegy mean to you, and how do you choose who to elegize?

FP: Yes, death is certainly one of the themes that haunt my work and, indeed, my life. But I don’t mean that in a negative sense. I very much love being alive—but I am not afraid of death, either. Among other things, I love cemeteries for the same reason I love to write elegies. Cemeteries are filled with stories and poems. But I don’t know about most of those. The stories I do know of are those of families, friends, and, of course, the “famous” dead. Being interested in the English Romantics (their lives even more than their work), the Pre-Raphaelites, and incidents from history, I find it natural to turn to those topics as subject matter for my poems.

Too, we’re all going to die one day. And this fact is reason enough to write about death—about what it means or could mean. Death is one of the “Great Topics” to write about, just as love and sex are.

HFR: What about the Romantics draws you to them? What kind of relationship or exchange do you see between poetry and painting?

FP: I’m attracted by some of the poetry written by the English Romantics (particularly the second generation, which would include Shelley, Keats & Byron). But, for the most part, I am fascinated by their lives. There was Lord Byron who was deemed “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Here was a man born with a clubfoot who ended up swimming the canals of Venice to rendezvous with his lovers. He drank vinegar to control his weight and to give himself a more pallid complexion. Tormented by his love for his half-sister and his desire for young men, he exiled himself from England and ended up dying of fever in Greece. His heart was removed and kept there while his body was sent back to England in a barrel of liquor. What’s not to love?

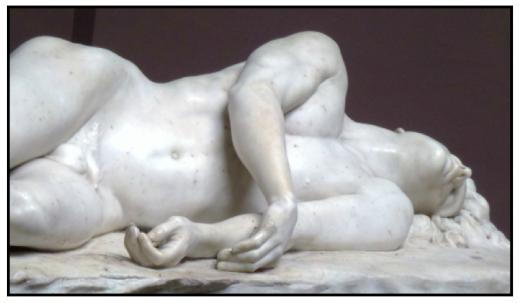

Then there’s Shelley who was described as possessing an almost otherworldly beauty and yet he had this simply awful voice. In his youth, he was a self-described atheist who was kicked out of Oxford for his essay, “The Necessity of Atheism.” Later in life, his spiritual beliefs could best be described as pantheistic. He was a believer in free love, and a man whose second wife penned Frankenstein during one incredible summer spent in Geneva with Lord Byron as their companion. And, if what most people speculate is correct, he met his death by drowning with uncanny calm. Ironically, there’s a breathtakingly beautiful statue of him at Oxford—it depicts the dead poet, nude and cast upon the Italian shore.

HFR: How do you know whose voice you are writing in? What elements make a voice sound authentic to you in your poems?

FP: Without trying to sound flip, I know whose voice I am writing in because it’s the voice I’ve chosen to write in. Or the voice that has chosen me to be its scribe.

Authenticity is elusive. In a sense, I have only my imagination to guide my hand. But there’s another, more mystical aspect, which is almost a kind of possession or surrender. I try to allow the personality of the individual to flow through my hands. In the same way, I try to inhabit historical events I might be writing about. Again, the aim is to paint a picture for myself and for my readers. If I achieve that—a vivid picture—I guess that’s authenticity.

HFR: The second section of Out of Eden consists entirely of elegies, ranging from poems about Keats, to Oscar Wilde, to Isadora Duncan. In the second section of The Rapture of Matter you elegize Shelley, your cousin, your father, mountain climbers, and Mike, a young man who commits suicide. What does the elegy mean to you, and how do you choose who to elegize?

FP: Yes, death is certainly one of the themes that haunt my work and, indeed, my life. But I don’t mean that in a negative sense. I very much love being alive—but I am not afraid of death, either. Among other things, I love cemeteries for the same reason I love to write elegies. Cemeteries are filled with stories and poems. But I don’t know about most of those. The stories I do know of are those of families, friends, and, of course, the “famous” dead. Being interested in the English Romantics (their lives even more than their work), the Pre-Raphaelites, and incidents from history, I find it natural to turn to those topics as subject matter for my poems.

Too, we’re all going to die one day. And this fact is reason enough to write about death—about what it means or could mean. Death is one of the “Great Topics” to write about, just as love and sex are.

HFR: What about the Romantics draws you to them? What kind of relationship or exchange do you see between poetry and painting?

FP: I’m attracted by some of the poetry written by the English Romantics (particularly the second generation, which would include Shelley, Keats & Byron). But, for the most part, I am fascinated by their lives. There was Lord Byron who was deemed “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Here was a man born with a clubfoot who ended up swimming the canals of Venice to rendezvous with his lovers. He drank vinegar to control his weight and to give himself a more pallid complexion. Tormented by his love for his half-sister and his desire for young men, he exiled himself from England and ended up dying of fever in Greece. His heart was removed and kept there while his body was sent back to England in a barrel of liquor. What’s not to love?

Then there’s Shelley who was described as possessing an almost otherworldly beauty and yet he had this simply awful voice. In his youth, he was a self-described atheist who was kicked out of Oxford for his essay, “The Necessity of Atheism.” Later in life, his spiritual beliefs could best be described as pantheistic. He was a believer in free love, and a man whose second wife penned Frankenstein during one incredible summer spent in Geneva with Lord Byron as their companion. And, if what most people speculate is correct, he met his death by drowning with uncanny calm. Ironically, there’s a breathtakingly beautiful statue of him at Oxford—it depicts the dead poet, nude and cast upon the Italian shore.

|

I could go on, but I think you get the picture.

The Pre-Raphaelites, like the English Romantics who rebelled against the norms of their day, produced a number of astonishing works of art. I find many of them terribly inspiring. And that leads to your question about the relationship between art and poetry. I have always said I am a frustrated painter. If I had the ability to paint I don’t think I’d ever write another poem because my paintings would express my thoughts so much more vividly than my words ever could. I think people who |

have the ability to express things without words—artists, musicians, dancers—are the most blessed. For me, and perhaps for other writers, we are artists without brushes. We must paint or dance or sing with language. And that is what I always seek to do. I guess a succinct answer to your question would be that poetry expresses in words what art expresses without need of words.

HFR: Your obsessions are cemeteries and saints. In fact, you are currently writing a series of saint poems. How did you arrive at these obsessions? What do they mean for you?

HFR: Your obsessions are cemeteries and saints. In fact, you are currently writing a series of saint poems. How did you arrive at these obsessions? What do they mean for you?

|

FP: Yes, my next book will contain a hagiography as one of its sections. Being raised Roman Catholic has everything to do with my obsessions. It’s really not very surprising. Some of the earliest memories I have involve images which surrounded me in church or at Catholic school—the half-nude figure of Jesus nailed to a cross, stained glass windows populated by angels and demons, saints holding various instruments of torture which were used to dispatch their souls to paradise. A few specific examples would be Saint Catherine of Alexandria standing by a spike-studded wheel upon which she was to be tortured. Saint Lawrence roasting on an iron grill, and Saint Lucy holding a plate upon which rest two eyes (representing her own, which were supposedly plucked out by order of Diocletian). The women, of course, were always gorgeous and otherworldly. And the stories were titillating—all these beautiful young virgins being disrobed! Or the thinly-veiled sexual frustration conveyed in tales of young nuns drinking from the wound in Jesus’ side. There’s such a weird mix of eroticism and spirituality. I think it had a profound influence on me as a person and as a poet.

|

My love of cemeteries is somewhat connected to all of this, I suppose, since Catholicism puts such great emphasis on death. Cemeteries remind us of our mortality, but that isn’t necessarily a negative thing. They are places of peace, reflection and calm. The old Victorian-types are also frequently quite beautiful—filled with breathtaking statuary, mourning figures…even a good number of nudes.

HFR: There is a lot of Catholic imagery in Out of Eden, beginning with the image of the Barbie/Joan of Arc/nun burning in the house’s fireplace to Biblical notions of the Fall, to the origins of the Devil. In The Rapture of Matter you speak of nuns, saints, cemeteries—and often this Catholic imagery is connected with sexuality. What draws you to this collection of images and what keeps you coming back to it?

FP: You’re right. I am actually obsessed with all of the things you mentioned. I guess the origin of that springs from the impressions I got as a child. Having attended parochial schools all the way through high school, I was immersed in all the strange, gory and, at least to my mind, enormously erotic imagery that is part and parcel of the Roman Catholic Church. I don’t think kids nowadays experience it in the same way I did as a child in the 60s and 70s. Nuns at that time were still, for the most part, fully-habited. They were beautiful and mysterious to me, seeming to float down the polished terrazzo halls of my school and church in floor-length black dresses, their veils drifting behind them, rosaries clicking at their waists. I don’t know, maybe I’m twisted, but I found them very alluring. Then there were all the stories I mentioned earlier. I didn’t read regular children’s tales when I was growing up. Well, I guess I read some Dr. Seuss, but that’s about it. I was immersed in beheadings, burning at the stake, crucifixion, flogging, hot brands, et cetera. As I said, it definitely leaves an impression.

HFR: There is a lot of Catholic imagery in Out of Eden, beginning with the image of the Barbie/Joan of Arc/nun burning in the house’s fireplace to Biblical notions of the Fall, to the origins of the Devil. In The Rapture of Matter you speak of nuns, saints, cemeteries—and often this Catholic imagery is connected with sexuality. What draws you to this collection of images and what keeps you coming back to it?

FP: You’re right. I am actually obsessed with all of the things you mentioned. I guess the origin of that springs from the impressions I got as a child. Having attended parochial schools all the way through high school, I was immersed in all the strange, gory and, at least to my mind, enormously erotic imagery that is part and parcel of the Roman Catholic Church. I don’t think kids nowadays experience it in the same way I did as a child in the 60s and 70s. Nuns at that time were still, for the most part, fully-habited. They were beautiful and mysterious to me, seeming to float down the polished terrazzo halls of my school and church in floor-length black dresses, their veils drifting behind them, rosaries clicking at their waists. I don’t know, maybe I’m twisted, but I found them very alluring. Then there were all the stories I mentioned earlier. I didn’t read regular children’s tales when I was growing up. Well, I guess I read some Dr. Seuss, but that’s about it. I was immersed in beheadings, burning at the stake, crucifixion, flogging, hot brands, et cetera. As I said, it definitely leaves an impression.

HFR: Is there any conflict for you, having been raised in a “stifling” Catholic culture and then turning to poetry, which primarily seeks to expose and understand human nature?

FP: I was raised in that culture. I never internalized it. On some level, even when my thinking wasn’t particularly sophisticated, I couldn’t swallow that belief system. What I responded to—and still do—is the art and symbolism, the candles, incense, stained glass and, of course, the stories of saints. I respond to the erotic aspects of the religion, too, which are there, even if most people don’t see it or care to admit it.

Anyway, as the years passed, and I could more thoroughly analyze things, I not only fully rejected Catholicism, I also rejected its tendency to celebrate sexuality only within the confines of what it determined to be “normal” and “acceptable.”

So there was never any conflict for me—but I was left with a determination to write against that stifling kind of theology. That is one of the reasons I write revisionist poems dealing with such topics.

FP: I was raised in that culture. I never internalized it. On some level, even when my thinking wasn’t particularly sophisticated, I couldn’t swallow that belief system. What I responded to—and still do—is the art and symbolism, the candles, incense, stained glass and, of course, the stories of saints. I respond to the erotic aspects of the religion, too, which are there, even if most people don’t see it or care to admit it.

Anyway, as the years passed, and I could more thoroughly analyze things, I not only fully rejected Catholicism, I also rejected its tendency to celebrate sexuality only within the confines of what it determined to be “normal” and “acceptable.”

So there was never any conflict for me—but I was left with a determination to write against that stifling kind of theology. That is one of the reasons I write revisionist poems dealing with such topics.

HFR: More broadly speaking, what’s your relationship to the Biblical text? The speaker of “One Who Hears,” is Lot’s wife. “Out of Eden” begins with Adam and Eve and comes to an end after considering Isaac. The cover of The Rapture of Matter features St. Theresa’s Ecstasy by Bernini. The Catholic imagery in Rapture, in fact, culminates when the Archangel Gabriel visits Mary in “The Grace of Conversion”—“he presses burning lips to my ear, whispers, ‘Most-highly-favored.'”

FP: My relation to Biblical text is…uneasy, at best. The use I find for most of the tales is in the retelling, in making them into something other than what they might have been intended to be. I’m a revisionist. The story of Abraham and Isaac is a good example. I find it insulting to any concept of “deity” that he/she would be accused of testing the faithfulness of his/her creation by demanding the sacrifice of one’s own child. My poem tries to point out what’s wrong with that idea without clubbing the reader over the head. “Out of Eden” is another poem which has, at its heart, a desire for revision. Maybe it wasn’t such a bad idea to want to get out of a kingdom ruled by a deity such as the one described in the Old Testament—a god of vengeance and jealousy. A god who throws temptation before his creation and then condemns them for succumbing. A god who, finally, is more of a spoiled brat than a being we’d choose to love.

FP: My relation to Biblical text is…uneasy, at best. The use I find for most of the tales is in the retelling, in making them into something other than what they might have been intended to be. I’m a revisionist. The story of Abraham and Isaac is a good example. I find it insulting to any concept of “deity” that he/she would be accused of testing the faithfulness of his/her creation by demanding the sacrifice of one’s own child. My poem tries to point out what’s wrong with that idea without clubbing the reader over the head. “Out of Eden” is another poem which has, at its heart, a desire for revision. Maybe it wasn’t such a bad idea to want to get out of a kingdom ruled by a deity such as the one described in the Old Testament—a god of vengeance and jealousy. A god who throws temptation before his creation and then condemns them for succumbing. A god who, finally, is more of a spoiled brat than a being we’d choose to love.

|

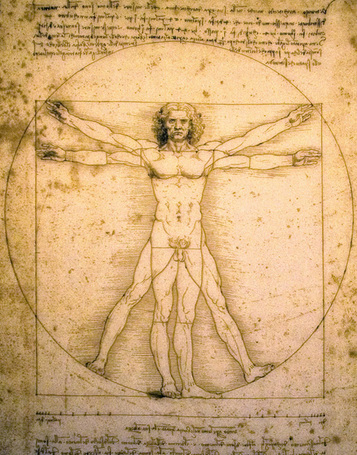

HFR: Out of Eden is preoccupied with the physical; in fact, it opens with a quote from Gautier that claims the “body [is] as beautiful as the soul” and culminates in “Each Bone of the Body” and “NDE” (Near Death Experience). The poems in this collection seem to concern methods of transcending the body. In poems where an individual dies, the death is not necessarily tragic nor an ending; instead, it is portrayed as an opportunity for the spirit to be released.

FP: I guess the driving force behind the book isn’t so much a desire to transcend the physical as it is a way of trying to point out there really is no line of delineation between the physical and the spiritual—they’re just two sides of the same coin. I want to celebrate the physical, not subjugate it. But more than anything, the poems want to fight against the idea this life is futile or that being human is somehow less than desirable. HFR: The Rapture of Matter explores destruction and ruin almost obsessively—the destruction of the horses in “Horse Latitudes.” The burning house. The ice cave melting. Ruined |

music. Waterlogged photographs. In “What the Heart Tells Us,” you write, “I’d play Jehovah, solemnly pronouncing, let there be// a great flood, as I turned on the hose, felt the mud/ slide beneath me. Mesmerized by disaster, I watched// ants struggle in the current.”

FP: Well, ruin is what we must contend with. Death and ruin. At the same time, I think there’s reason to celebrate impermanence and imperfection. There’s something to be said for the necessity of struggle, even if it’s only that it makes us appreciate the good times that much more.

HFR: In The Rapture of Matter you complicate perfection. You associate perfection with belief—and with the creative act. In “This Is Not a Sad Poem,” you write: “Listen. I have a secret./ What really matters is something other than/ ice, seasons, hours, the belief in perfection.” Later, in the poem, “St. Theresa’s Ecstasy,” you speak of the “perfect forms” of religious art. In “Heaven,” finally, you write, “where love is happening without needing/ to believe in its own perfection.”

FP: It’s rather a paradox, isn’t it? There’s something perfect about imperfection, if you will. I find imperfections more interesting, many times, than whatever might be considered “perfect.” Take a woman’s body as an example. If you gave me a choice of a woman with absolutely no physical flaws (if there is such a woman) or one with a scar here or there—or maybe a feature out of balance with the rest of her form—I’d be more interested in the “imperfect” woman because the imperfection makes her more fully human, endearing…approachable. Perfection doesn’t belong to the physical world and much of my work is engaged with the physical world.

HFR: It’s interesting that you’re attracted to the “flawed” or the “imperfect” when you consider it next to a religion like Catholicism which deifies the absence of flaws.

FP: Basically, what Catholicism teaches is that we are all hopelessly flawed by sin and the only way around that is to put faith in Jesus. I believe we need to redeem ourselves—not from hell or anything like that, but from those things which keep us from being the best people we can be.

But when I talk about flaws, I’m painting on a much broader canvas than what might be embraced in the Catholic view. If “sin” is included in that, I would have to define it as a failure to live up to our highest nature. And that’s not necessarily the sort of thing I’m talking about when I mention feeling there is something to praise in flaws. What I’m primarily referring to are imperfections in the body itself and in our experiences. It seems easier to relate to that sort of brokenness or flaw because that is the natural state of things on this planet.

In my poetry, I’m only interested in what is imperfect—life, faith, even sex. Whatever lives, dies. Whatever we believe in still has some element of doubt. And even the pleasure of sex is sometimes tinged with pain…and, if not, it’s still only temporary and so, flawed.

In a way, I think imperfection is what keeps us going. It makes us strive for perfection—even though we will never attain it.

HFR: Loss colors almost all of your poems. The loss of love. The loss of the body. The loss of life. The loss, truly, of Eden?

FP: Loss is an unavoidable reality. It’s part of what it is to be human and I’m not interested in writing poems that seek to ignore that. If nothing is at stake in one of my poems then I have failed in my task as a poet because, in my philosophy, a poem that doesn’t, on some level, seek to ask hard questions, or consider hard answers, isn’t much of a poem.

HFR: In many of your poems, the body is associated with knowledge, lessons, teaching and learning. “Denali” begins, “At 18,000 feet, you’re dead and this/ is the body’s cruelest lesson; to hold you// in my arms and still be powerless/ to free you from this throat of ice.” One of your poems is entitled “What the Heart Tells Us,” and another, “The Wisdom of the Body.” At the end of “Walkingstick,”—again, learning is linked with death of the body. Later, you write that the drowned girl “taught me death is beautiful” and in your poem “The Cave of Saint Rita,” you write “her flesh understood its exaltation.” How are you connecting knowledge with the body?

FP: Well, ruin is what we must contend with. Death and ruin. At the same time, I think there’s reason to celebrate impermanence and imperfection. There’s something to be said for the necessity of struggle, even if it’s only that it makes us appreciate the good times that much more.

HFR: In The Rapture of Matter you complicate perfection. You associate perfection with belief—and with the creative act. In “This Is Not a Sad Poem,” you write: “Listen. I have a secret./ What really matters is something other than/ ice, seasons, hours, the belief in perfection.” Later, in the poem, “St. Theresa’s Ecstasy,” you speak of the “perfect forms” of religious art. In “Heaven,” finally, you write, “where love is happening without needing/ to believe in its own perfection.”

FP: It’s rather a paradox, isn’t it? There’s something perfect about imperfection, if you will. I find imperfections more interesting, many times, than whatever might be considered “perfect.” Take a woman’s body as an example. If you gave me a choice of a woman with absolutely no physical flaws (if there is such a woman) or one with a scar here or there—or maybe a feature out of balance with the rest of her form—I’d be more interested in the “imperfect” woman because the imperfection makes her more fully human, endearing…approachable. Perfection doesn’t belong to the physical world and much of my work is engaged with the physical world.

HFR: It’s interesting that you’re attracted to the “flawed” or the “imperfect” when you consider it next to a religion like Catholicism which deifies the absence of flaws.

FP: Basically, what Catholicism teaches is that we are all hopelessly flawed by sin and the only way around that is to put faith in Jesus. I believe we need to redeem ourselves—not from hell or anything like that, but from those things which keep us from being the best people we can be.

But when I talk about flaws, I’m painting on a much broader canvas than what might be embraced in the Catholic view. If “sin” is included in that, I would have to define it as a failure to live up to our highest nature. And that’s not necessarily the sort of thing I’m talking about when I mention feeling there is something to praise in flaws. What I’m primarily referring to are imperfections in the body itself and in our experiences. It seems easier to relate to that sort of brokenness or flaw because that is the natural state of things on this planet.

In my poetry, I’m only interested in what is imperfect—life, faith, even sex. Whatever lives, dies. Whatever we believe in still has some element of doubt. And even the pleasure of sex is sometimes tinged with pain…and, if not, it’s still only temporary and so, flawed.

In a way, I think imperfection is what keeps us going. It makes us strive for perfection—even though we will never attain it.

HFR: Loss colors almost all of your poems. The loss of love. The loss of the body. The loss of life. The loss, truly, of Eden?

FP: Loss is an unavoidable reality. It’s part of what it is to be human and I’m not interested in writing poems that seek to ignore that. If nothing is at stake in one of my poems then I have failed in my task as a poet because, in my philosophy, a poem that doesn’t, on some level, seek to ask hard questions, or consider hard answers, isn’t much of a poem.

HFR: In many of your poems, the body is associated with knowledge, lessons, teaching and learning. “Denali” begins, “At 18,000 feet, you’re dead and this/ is the body’s cruelest lesson; to hold you// in my arms and still be powerless/ to free you from this throat of ice.” One of your poems is entitled “What the Heart Tells Us,” and another, “The Wisdom of the Body.” At the end of “Walkingstick,”—again, learning is linked with death of the body. Later, you write that the drowned girl “taught me death is beautiful” and in your poem “The Cave of Saint Rita,” you write “her flesh understood its exaltation.” How are you connecting knowledge with the body?

|

FP: The body does have its lessons to teach. It’s the seat of our senses, for one thing, and thus a direct means of coming to understand much of the world around us. And there is also a very real way in which the body knows things we don’t. It can heal itself. Our hearts circulate our blood without need of assistance from us; our lungs bring oxygen to our blood without any need of intervention on our part. It’s fascinating and mysterious.

HFR: In a similar vein, you often speak of bodies with secrets inside of them—like the girl in “Pentimento” who is pregnant and has an abortion. The “secret swell of her belly” becomes “the girl she once was bleeding through.” In “Elegy, 1822,” you speak of Shelley’s lips that are “dark with their secret.” A few lines later, as Byron is swimming out to his boat, you write, “Something feels/ endless inside him.” In the poem, “Heaven,” you write, “What your body’s saying is that you want/ to tell a secret.” In "What the Blue Jay Said," the first line reads: "There's a stranger inside him." Later in that poem, "Something within |

wants/ release” and “They buried a secret inside him.” The poem ends with him tearing out his own heart and “bellowing his final breath, Take it back. It’s yours."

FP: Again, it’s the idea of all the things we don’t know, the things our bodies do "know." Our bodies contain all manner of secrets. Sometimes we discover them. Oftentimes, we do not.

HFR: The endings of your poems—they are either deeply hopeful, or quite dark. Many end with light, flying, the sun, circles, touching, belief, love, and salvation. Others end with blisters, uncertainty, blood, strangers, silence, regret, final breaths, approaching thunder, goodbye, darkness, nothing. The only two poems in Rapture with a very open ending, an equivocal ending, are the first and the last poems. The first ends with “as it shifts north/ northwest.” Your final poem ends with the words “sweet as sin."

FP: I don’t pretend to know the answers to the big questions any more than the next guy. It’s inevitable that my poems reflect this. Sometimes the positive side seems true to me. Other times, it doesn’t.

I guess the short answer is that I just don’t know.

HFR: You’ve mentioned that you felt Out of Eden is a stronger book than The Rapture of Matter. To me, Out of Eden feels much denser, carrying heavier emotional and physical burdens. Can you talk a bit about your personal connection to those books now, and perhaps touch on your relationship to a kind of “density” in your work? What changes or decisions did you make that prompted the change from the first book to the second?

FP: Well, Rapture was the manuscript I completed as part of the requirement for earning my MFA. Given that I really only started writing seriously around 1986, and that manuscript was completed and accepted for publication in 1990, I really wasn’t a very mature writer. Today, when I look at Rapture, with the exception of a few poems, I’m not terribly impressed by the work. I find myself wishing I’d done things differently. Of course, at the time, that was the best I could do. I’m not happy about it—but that’s simply the case.

Out of Eden reflects the next step in my growth as a poet. I had the tools to work with in my first book, but I wasn’t sure of myself with regard to how best to use them. I’m still not done growing as a poet, and, as I work on my third manuscript, I hope I am moving a little further along in my ability to paint with language. Part of that process has manifested itself in the increased density of the poems. To continue with the analogy of the painter, I guess I’m layering more paint, going for more texture. And that doesn’t necessarily mean the poems are getting longer. I think a poem can be short and still quite dense.

I didn’t make a conscious decision to change things from the first book to the second. It was simply a matter of growing as a writer. And I don’t know that I’ll ever really be fully satisfied with my poetry. I constantly wrestle with feeling I’m not getting things right. And I always worry that the poem I just finished will be the last I’ll ever be able to create. I know some people find it relatively easy to write, but I am not one of them—that’s for certain!

FP: Again, it’s the idea of all the things we don’t know, the things our bodies do "know." Our bodies contain all manner of secrets. Sometimes we discover them. Oftentimes, we do not.

HFR: The endings of your poems—they are either deeply hopeful, or quite dark. Many end with light, flying, the sun, circles, touching, belief, love, and salvation. Others end with blisters, uncertainty, blood, strangers, silence, regret, final breaths, approaching thunder, goodbye, darkness, nothing. The only two poems in Rapture with a very open ending, an equivocal ending, are the first and the last poems. The first ends with “as it shifts north/ northwest.” Your final poem ends with the words “sweet as sin."

FP: I don’t pretend to know the answers to the big questions any more than the next guy. It’s inevitable that my poems reflect this. Sometimes the positive side seems true to me. Other times, it doesn’t.

I guess the short answer is that I just don’t know.

HFR: You’ve mentioned that you felt Out of Eden is a stronger book than The Rapture of Matter. To me, Out of Eden feels much denser, carrying heavier emotional and physical burdens. Can you talk a bit about your personal connection to those books now, and perhaps touch on your relationship to a kind of “density” in your work? What changes or decisions did you make that prompted the change from the first book to the second?

FP: Well, Rapture was the manuscript I completed as part of the requirement for earning my MFA. Given that I really only started writing seriously around 1986, and that manuscript was completed and accepted for publication in 1990, I really wasn’t a very mature writer. Today, when I look at Rapture, with the exception of a few poems, I’m not terribly impressed by the work. I find myself wishing I’d done things differently. Of course, at the time, that was the best I could do. I’m not happy about it—but that’s simply the case.

Out of Eden reflects the next step in my growth as a poet. I had the tools to work with in my first book, but I wasn’t sure of myself with regard to how best to use them. I’m still not done growing as a poet, and, as I work on my third manuscript, I hope I am moving a little further along in my ability to paint with language. Part of that process has manifested itself in the increased density of the poems. To continue with the analogy of the painter, I guess I’m layering more paint, going for more texture. And that doesn’t necessarily mean the poems are getting longer. I think a poem can be short and still quite dense.

I didn’t make a conscious decision to change things from the first book to the second. It was simply a matter of growing as a writer. And I don’t know that I’ll ever really be fully satisfied with my poetry. I constantly wrestle with feeling I’m not getting things right. And I always worry that the poem I just finished will be the last I’ll ever be able to create. I know some people find it relatively easy to write, but I am not one of them—that’s for certain!